DNDSR designs

Array data structure

Array<>

The basic Array<T,...> data container is a data container designed for MPI-based distributed parallelism. Element type T has to be trivially-copyable.

| |

| _row_size>=0 | _row_size==DynamicSize | _row_size==NonUniformSize | |

|---|---|---|---|

| _row_max>=0 | TABLE_StaticFixed | TABLE_Fixed | TABLE_StaticMax |

| _row_max==DynamicSize | TABLE_StaticFixed_row_max ignored | TABLE_Fixed_row_max ignored | TABLE_Max |

| _row_max==NonUniformSize | TABLE_StaticFixed_row_max ignored | TABLE_Fixed_row_max ignored | CSR |

Underlying data layout: 1-D indexing / 2-D indexing.

For fix-sized 2-D tables, it is basically a row-major matrix with the first index potentially globally aware. For variable-sized 2-D tables, it is a CSR-indexed variable array.

ParArray<> and ArrayTransformer<>

Parallel communication: ParArray<...> and ArrayTransformer<...>.

ParArray is Array with global indexing info. Generally use a globally (inside the MPI communicator) rank-based contiguous indexing.

Operations on ParArray should be collaborative (inside MPI comm).

| |

ArrayTransformer<...> relates two ParArray<...> together by defining an all-to-all style arbitrary index mapping.

| |

In PDE solvers, most used critical for ghost mesh/point/cell data, so the mapping is called ghost mapping.

Conceptually:

| |

We define that IndexFather can be scattered in each rank (section) or even overlapping, and IndexSon must be like 0:N.

Therefore, transforming from father to son (or main to ghost) is unique, but not so backwards.

We name father->son parallel data transferring pull, and push when reversed.

General communication procedures:

| |

For persistent data transfers:

| |

To ease the use of underlying data, we have ArrayEigenMatrix<...> for AoS style floating point DOF storage, and ArrayAdjacency<...> for integer index storage. They inherit from ParArray<>.

ArrayPair<>

Sometimes a pair of father and son are always bound together to form a main vs. ghost pair.

To ease the complexity of data indexing in the ghost region, ArrayTransformer’s ghost indexing can be stored as a local version of adjacency table. We define that the local index of ghost is appended to the main part, so that a local adjacency table can be logically valid and compact. This indexing and pairing is realized by the wrapper ArrayPair<>.

| |

DeviceView

The hierarchy of Array data containers can generate a trivially-copyable device view objects that only hold pointers and sizes and have data-accessors methods that never mutate the array shape.

The device views may hold device pointers, which make them perfectly usable on CUDA devices.

Some shared data, like CSR indexes can be forced into a raw-pointer to reduce overhead (on CPU).

Device views should always be generated and used in a local procedure during which the array shapes are never mutated.

Asynchronous procedures

A direct design:

| |

A more sophisticated design:

| |

A more robust interface: TASK BASED

Task based scheduling

1. Core abstraction: tasks, data regions, and access modes

1.1 Data objects with regions

Instead of thinking in terms of arrays + ghost exchange, define logical data objects with regions:

| |

The runtime understands that:

a_mainis locala_ghostrequires MPI communication

1.2 Tasks with access descriptors

Each task declares what data it accesses and how:

| |

This is the only information the scheduler needs.

2. Communication becomes implicit tasks

MPI communication is not special — it is just another task:

| |

The runtime inserts this automatically when:

A task reads a region that is not locally available

3. DAG construction (formal model)

Each iteration builds a directed acyclic graph (DAG):

Nodes

- Compute tasks

- Communication tasks (MPI Isend/Irecv)

- Optional memory transfer tasks (H2D, D2H, disk I/O)

Edges

T1 → T2if T2 needs data produced by T1

4. Scheduler semantics (key rules)

A runtime loop looks like this:

| |

Task readiness condition

A task is ready if:

- All its input regions are available

- No conflicting write is in flight

5. Pseudo-code: user-facing API

| |

6. Runtime-side pseudo-code

6.1 Dependency resolution (for distributed memory)

As non-local dependency should automatically create some comm tasks:

| |

6.2 Communication task

| |

Completion of CommTask marks region as available.

7. Exploiting task parallelism within a rank

Once everything is tasks, intra-node parallelism is automatic:

| |

Python interface

DNDSR has a Python interface that allow orchestration of the computing via Python.

Core concept: Array, ParArray, ArrayTransformer, ArrayPair are exported to Python via pybind11.

In python: provide (CPU-side) data accessors (mostly for testing or initializations).

Export mesh and solver interface, including mesh data (adjacency and geometry), solver data (FV’s geometric data), relevant methods, computing methods (kernels).

To collaborate with other libraries:

- numpy is natural, via buffer protocol

- mpi4py is compiled in the same MPI env.

- cupy is compiled in the same CUDA env (runtime linking?)

DNDSR CUDA kernels

DNDSR provide CUDA capabilities.

Each Array actually holds data via a host_device_vector<T> object.

host_device_vector is like std::vector or thrust::device_vector but provides a unified interface.

It uses an underlying DeviceStorageBase for byte storage that may be implemented on various devices.

| |

Array objects then can do to_device… and to_host to initiate H2D / D2H data transfer.

Currently no async memcpy interface provided.

To pass device-stored Array objects (and derived/combined ones) to CUDA kernels, they provide device view generators that generate trivially copyable XXDeviceView objects.

To reduce the size of

Arraydevice views, currentlystd::conditional_t<...>is used for its data fields. If some pointer/size is not needed, the data field is set toEmptytype. Due to C++ standard, a simple empty struct still takes 1 byte as member data, could use[[no_unique_address]]if upgrade to C++ 20.

The device view objects can be passed directly as parameters of __global__ functions.

However, one limitation is that some objects composed of a large amount of ArrayXXXs can generate huge device view objects. For example, EulerP::EvaluatorDeviceView<B>, which holds an FV view and a mesh view, takes up 3496 bytes because they hold/reference dozens of ArrayPairs.

In such cases, nvcc might complain about the parameter size being too large. A safe way is to store the view into global memory before calling the kernel and passing the global pointer.

For huge-view storage, as they do not change (during kernel), and are basically broadcasted, using constant memory should be better. However, managing the total constant memory size per CUDA context need more infrastructure.

Currently, for CUDA-resided

Arrays,ArrayTransformeris only able to handle MPI communication via a CUDA-aware MPI.

EulerP CUDA implementation

See the test here: EulerP CUDA tests

Currently, for 2nd-order finite-volume kernels, we use simple one-thread-per-point parallelism.

Each thread writes to one point, write buffer pattern is known.

Each thread reads several points, read buffer pattern is decided by the mesh adjacency (graph).

Computing density is quite low, almost 1 ~ 3 op / 8 bytes ! Read pattern is unstable, not easy to reuse read buffer. Use graph reordering to improve locality for L2-cache friendliness ?.

What we can do first?

Write coalescing optimization

The DOFs of DNDSR are packed as AoS style: $N\times 5$ row-major matrix, where threads are mapped onto $N$’s dimension for computing.

For gradients, this becomes $N\times 15$.

If extend to higher order methods, the row size could be much larger.

Some auxiliary arrays (and extended scalar DOFs) are stored as SoA style, but the primary N-S Dofs are packed together as they are always used as a whole.

Moreover, as the solver is designed to be an N-S coupled solver, block-sparse matrix must accept a SOA-style array as DOF.

Therefore, no cheap coalescing, need manual shuffling. A rather generic wrapped __device__ function for this optimization:

| |

This is thread-block level synchronized call, do not diverge on the call.

Template instantiation divergence could cause serious problems, the safest pattern is to call only once.

Effect: 3.2x speed boost, 2.8x power efficiency boost.

CUDA

Sort

Bitonic

Purely in-block sort: bitonic sort

| |

Radix

- For bit 0, get bucket counts:

total_zerosand predicateis_zero[i] - scan predicate: prefix sum (exclusive)

prefix_zero[i] - scatter:

| |

- Do bit 1 sorting in segments

out[0:total_zeros], out[total_zeros:] - …

Optimizations

Using b bits together. b=4, 16 buckets.

Each element belongs to 1 bucket.

Block-wise histogram: hist[iBlock][iBucket]

Global block-hist: hist_g[iBucket] -> prefix sum of the 16 sized array: bucket_start[iBucket]

Prefix sum on block-hist: hist_ps[iBlock][iBucket]

Then element-wise prefix-sum per-block (in-block scanning) pre_num[iBucket][tid] (only locally used so no actual global mem).

The new index: pre_num[iBucket][tid] + hist_ps[iBlock][iBucket] + bucket_start[iBucket]

Block scanning

| |

Working example

| |

Reduction

Tree reduction

In-warp:

| |

| |

If reducing integer, using atomicAdd to reduce block results can be very fast.

If reducing float, using atomicAdd is ok but is non-deterministic when number is large.

Use recursive reductionSum_block for a full tree reduction.

A full example

| |

Mutex

atomicCAS( ptr, compare, val) does this: compare if ptr == compare, if true, store val asptr. The return value is the old *ptr value. The whole process is atomic. We can get a mutex:

| |

using this mutex one-per-block should be OK, one-per-thread could lead to deadlock on older GPUs (?). See CUDA C++ Programming Guide section 7.1.

GEMM kernel

We only discuss the design of not using distributed shared memory and wrap specialization.

The LeetGPU code

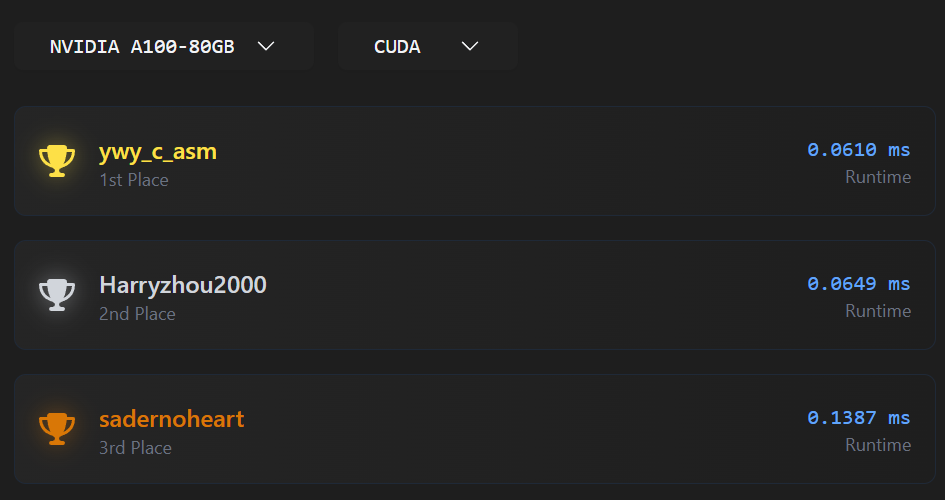

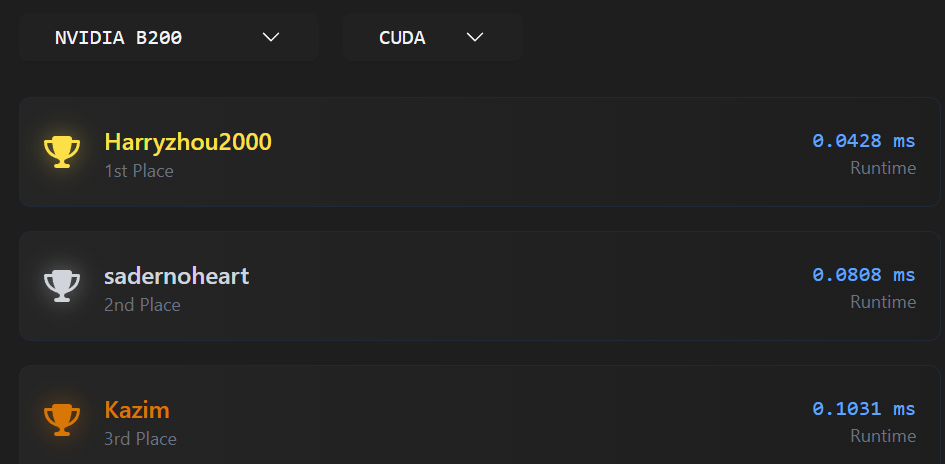

we got second place for A100 and H200 and first place on B200 with this code… it should be only 1/3 of CUBLAS (with 4096**3 case) on A100

Basic definitions

head:

| |

Tile sizes:

| |

We use $4\times 8$ data for each warp loader (logically), and $2\times 2$ warps in the thread block.

The thread blocks logically load $(4\times 2) \times (2 \times 2)$ different tiles.

Guaranteed to be a multiple of $16\times 16$ for the sake of WMMA.

K-direction tile sizes:

| |

Derived sizes:

| |

WMMA’s computing sizes

| |

HGEMM skeleton

The hgemm kernel:

| |

Host driver

Driver code:

| |

Async loader

The loading procedure:

| |

For ragged load shifting rows:

| |

Epilogue and store

Store C to global (fused epilogue considering alpha and beta). How to optimize this?

| |

This

store_matrix_float_to_half_acchas bug: the scenario when ldc (lda in the args) unaligned not considered, causes CUDA alignment error.

Streams & Graph

A CUDA stream is a queue of operations (kernel launches, memcpys, events) that:

- Execute in issue order within the same stream

- May execute concurrently with other streams (if hardware allows)

Default stream

0orcudaStreamDefault- Historically synchronizes with all other streams (legacy behavior)

- Modern CUDA supports per-thread default stream (PTDS)

| |

| |

Stream Synchronization

| |

- Blocks host

- Heavy hammer

- Avoid in performance-critical paths

Stream Events

Record an event

| |

Make another stream wait

| |

Result

| |

- No host blocking

- The dependency is like inserted into the queues.

Event Sync

| |

Used when correctness requires host visibility.

A CUDA graph is:

A static DAG of GPU operations captured once and replayed many times

- Kernel launch overhead is non-trivial

- Repeated patterns are common (CFD timesteps, solvers)

- Graph replay is much cheaper than re-launching kernels

Nodes can be:

- Kernel launches

- Memcpy / memset

- Host functions

- Event record / wait

- Child graphs

Graph Construction: Stream capture

| |

Then:

| |

Graph Construction: Manual

| |

CUDA Performance Analysis

About the GEMM + nsight compute:

| |

Shows:

| |

For once of hgemm_wmma_cp_async, results:

| |

The cuBLAS result:

| |

MPI

Great target 👍 — for NVIDIA Developer Technology (DevTech) Intern, especially a system-level performance optimization role, MPI questions usually focus less on “write MPI from scratch” and more on performance reasoning, communication patterns, and interaction with GPUs / systems. Given your CFD + MPI background, you’re actually very well aligned.

Below is a structured list of common MPI interview questions, grouped by theme, with brief hints on what the interviewer usually wants to hear.

1. MPI Fundamentals (Warm-up / Sanity Check)

These verify you truly understand MPI beyond syntax.

What is MPI and why is it used instead of shared memory?

- Distributed memory model

- Scalability, portability, performance control

Difference between

MPI_SendandMPI_Isend?- Blocking vs non-blocking

- Progress, overlap, completion semantics

What does

MPI_Init/MPI_Finalizedo?- Process environment setup, communicator creation

What is a communicator?

MPI_COMM_WORLD- Context + group

- Why communicators matter for correctness and performance

Difference between rank and size?

MPI_Comm_rank,MPI_Comm_size

What happens if one rank does not call a collective?

- Deadlock / undefined behavior

2. Point-to-Point Communication (Very Common)

These often appear with deadlock or performance reasoning.

Explain eager vs rendezvous protocol

- Message size threshold

- Buffering vs handshake

- Why large messages can deadlock

Can

MPI_Senddeadlock? Give an example- Symmetric sends without matching receives

- Depends on message size / buffering

Difference between

MPI_Isend+MPI_WaitvsMPI_Send- Overlap potential

- Need to manage request lifetime

What does

MPI_Probedo? When would you use it?

- Unknown message size

- Dynamic communication patterns

- What is message matching in MPI?

(source, tag, communicator)- Why incorrect tags cause bugs

3. Collectives

Expect performance-oriented questions here.

- Difference between

MPI_Bcast,MPI_Scatter,MPI_Gather,MPI_Allgather

- Communication patterns

- Use cases in CFD / AI

- What is

MPI_ReducevsMPI_Allreduce?

- Rooted vs replicated result

- Cost difference

- Why is

MPI_Allreduceoften a bottleneck?

- Global synchronization

- Latency-dominated

- Scaling issues

- How is

MPI_Allreducetypically implemented?

- Tree-based

- Ring

- Rabenseifner

- Topology-aware algorithms

- When would you replace collectives with point-to-point?

- Irregular communication

- Partial participation

- Avoid global sync

4. Performance & Scalability (Very Likely)

This is core DevTech territory.

- Strong scaling vs weak scaling

- Fixed problem size vs fixed work per rank

- Why does MPI performance degrade at high core counts?

- Latency domination

- Network contention

- Synchronization

- Load imbalance

- What is communication–computation overlap?

- Non-blocking communication

- Progress engines

- Practical limitations

- How do you identify MPI bottlenecks?

- Profilers: Nsight Systems, VTune, mpiP

- Time in collectives

- Idle time / imbalance

- What is Amdahl’s Law vs Gustafson’s Law?

- Strong vs weak scaling interpretation

5. MPI + System Architecture (NUMA / Network)

NVIDIA loves system-level awareness.

- What is NUMA and why does it matter for MPI?

- Memory locality

- Rank placement

- First-touch policy

- How does process binding affect MPI performance?

- Core affinity

- Cache reuse

- Avoid oversubscription

- What is network topology awareness?

- Fat-tree vs dragonfly

- Intra-node vs inter-node communication

- Difference between intra-node and inter-node MPI communication

- Shared memory vs network

- Latency and bandwidth

6. MPI + GPU (Very Important for NVIDIA)

Even if you’re not a CUDA expert yet, expect these.

- What is CUDA-aware MPI?

- GPU pointers passed directly to MPI

- Avoid host staging

- How does GPU–GPU communication work across nodes?

- GPUDirect RDMA

- NIC ↔ GPU memory

- What are the benefits of CUDA-aware MPI?

- Lower latency

- Higher bandwidth

- Less CPU involvement

- How would you overlap MPI communication with GPU kernels?

- CUDA streams

- Non-blocking MPI

- Events for synchronization

- What happens if MPI is not CUDA-aware?

- Explicit

cudaMemcpy - Extra synchronization

- Performance penalty

7. CFD-Style MPI Questions (Your Advantage)

Interviewers often probe domain intuition.

- How is MPI typically used in CFD solvers?

- Domain decomposition

- Halo / ghost cell exchange

- Reductions for residuals

- Why are halo exchanges latency-sensitive?

- Small messages

- Frequent synchronization

- How would you optimize halo exchange?

- Non-blocking communication

- Packing

- Neighborhood collectives

- Overlap with interior computation

- What MPI pattern dominates CFD time-to-solution?

- Nearest-neighbor communication

- Global reductions

8. Debugging & Correctness

Often mixed with performance.

- Common MPI bugs you’ve seen

- Deadlocks

- Mismatched collectives

- Tag mismatches

- Incorrect buffer lifetimes

- How do you debug MPI deadlocks?

- Print rank-tag tracing

- Reduce to 2–4 ranks

- Use MPI correctness tools

RDMA ?

NCCL

Basics

1. Communicator

A communicator defines:

- Which GPUs participate

- Their ranks

- Their topology

Created once, reused across iterations:

| |

At system level:

- Expensive → cache it

- Initialization cost matters for short jobs

2. AllReduce (core AI primitive)

Used for:

- Gradient synchronization

- Model parameter aggregation

Mathematically:

| |

NCCL implements ring, tree, or hybrid algorithms depending on:

- Message size

- Topology

- Number of GPUs

3. Topology awareness (very important)

NCCL discovers system topology at runtime:

- GPU ↔ GPU (NVLink, PCIe)

- GPU ↔ NIC (NVLink-NIC, PCIe switch)

- NUMA domains

It builds communication rings/trees that:

- Prefer NVLink over PCIe

- Minimize PCIe root crossings

- Optimize NIC usage

👉 Bad topology → bad scaling

4. Intra-node vs Inter-node NCCL

Intra-node

- NVLink / PCIe

- Very high bandwidth, low latency

- Typically near-ideal scaling

Inter-node

Uses:

- InfiniBand (RDMA)

- Ethernet (RoCE)

GPU Direct RDMA (GDR) if enabled

Key system-level factors:

- NIC placement

- GPU-NIC affinity

- NUMA alignment

5. GPU Direct RDMA (GDR)

Allows:

| |

Benefits:

- Lower latency

- Higher bandwidth

- Less CPU overhead

System requirements:

- Supported NIC (e.g. Mellanox)

- Correct driver stack

- IOMMU / ACS settings matter

NCCL execution model

NCCL calls are asynchronous

Enqueued into a CUDA stream

Synchronization happens via:

- CUDA events

- Stream waits

Example (conceptual):

| |

👉 Enables communication–computation overlap

NCCL in AI frameworks

PyTorch

- Uses NCCL backend for

DistributedDataParallel - One NCCL communicator per process group

- Gradient buckets → AllReduce

Performance knobs:

- Bucket size

- Overlap on/off

- Stream usage

Multi-node training stack

Typical flow:

| |

MPI is often used only for:

- Rank assignment

- Environment setup

Common system-level performance issues

1. Wrong GPU–NIC affinity

Symptoms:

- Low bandwidth

- Unbalanced traffic

Fix:

- Bind processes correctly

- Match GPU closest to NIC

2. NUMA misalignment

Symptoms:

- High CPU usage

- Inconsistent iteration time

Fix:

- CPU pinning

- Correct process placement

3. Oversubscription

- Too many processes per socket

- Competes for PCIe / memory bandwidth

4. Small message sizes

- NCCL bandwidth not saturated

- Ring startup dominates

Common in:

- Small models

- Too many gradient buckets

NCCL APIs

1. Communicator & Initialization APIs

These define who participates in collectives.

Core communicator APIs

| |

ncclGetUniqueIdGenerates a unique ID (usually on rank 0, broadcast via MPI)ncclCommInitRankCreates a communicator for one rank

📌 System-level note

- Communicator creation is expensive

- Should be done once, reused across iterations

Multi-GPU per process

| |

- Used when one process controls multiple GPUs

- Common in single-node setups

Communicator teardown

| |

2. Collective Communication APIs (Core NCCL Value)

Most common collectives

| |

Full prototype (example: AllReduce)

| |

Supported reductions

| |

3. Group APIs (Latency Optimization)

Used to batch multiple NCCL calls.

| |

Example:

| |

📌 Why this matters

- Reduces launch and synchronization overhead

- Improves performance when launching many collectives

- Common inside DL frameworks

4. CUDA Stream Integration (Critical)

Every collective takes a:

| |

Meaning:

- NCCL ops are enqueued, not executed immediately

- They respect stream dependencies

- They can overlap with computation

Example:

| |

5. CUDA Graph Compatibility

NCCL collectives can be captured in CUDA Graphs.

Flow:

| |

📌 Benefits:

- Removes CPU launch overhead

- Important for short-iteration AI workloads

- Used in high-performance training loops

Point-to-point

NCCL does have point-to-point now.

Since NCCL 2.7+:

| |

These are:

- GPU-to-GPU

- CUDA-stream-aware

- NVLink / IB optimized

So pipeline parallelism can use:

ncclSend/Recv- CUDA IPC

- Or even CUDA memcpy (same node)

How pipeline parallelism is actually implemented

Option 1: NCCL Send / Recv (common today)

Forward:

| |

Backward:

| |

This is streamed, overlappable with compute.

Option 2: CUDA-aware MPI (less common in DL)

Used sometimes for:

- Inter-node activation passing

- Research frameworks

But:

- NCCL is preferred in production DL

Option 3: Collectives (less common for PP)

Some frameworks:

- Use

AllGatherinstead of send/recv - Especially when multiple next stages exist

6. Why NCCL collectives still matter in PP

Even in pipeline parallelism:

| Phase | Communication |

|---|---|

| Forward | Send activations |

| Backward | Send activation gradients |

| Optimizer | DP AllReduce |

| TP | AllReduce / ReduceScatter |

| MoE | AllToAll |

LLM

1. System-Level View: What Is an LLM?

At the highest level, a modern LLM is:

A large autoregressive sequence model that predicts the next token, trained on massive corpora, and deployed with aggressive parallelism and memory optimization.

Key properties:

- Autoregressive: predict

token_tgiventoken_<t - Token-based: text → tokens → embeddings

- Scale-driven: performance comes primarily from model/data/compute scaling

- GPU-first: designed around dense linear algebra

2. Model Family Level: Transformer-Based Models

Nearly all modern LLMs are based on Transformers, with variations.

Canonical examples

- GPT-3/4, LLaMA, Mistral, Qwen → Decoder-only Transformers

- PaLM, Gemini → Transformer variants

- Mixtral → Mixture-of-Experts Transformer

Why Transformers?

- No recurrence → parallelizable

- Attention → global context

- Works extremely well with matrix multiply accelerators

3. Macro Architecture: Decoder-Only Transformer

Most LLMs you’ll encounter are decoder-only:

| |

Important:

- No encoder

- Causal (masked) attention

- Same block repeated

Ntimes (e.g., 32–120 layers)

4. Transformer Block Anatomy (Critical)

Each Transformer block consists of:

| |

This is where 90%+ of compute happens.

5. Attention Mechanism (The Core Idea)

Scaled Dot-Product Attention

For each token:

| |

Properties:

- Quadratic complexity: O(seq²)

- Memory heavy (attention matrix)

- Dominates inference latency at long context

Causal Masking

- Prevents attending to future tokens

- Enables autoregressive generation

6. Multi-Head Attention (MHA)

Instead of one attention:

- Split into

hheads - Each head attends to different subspaces

| |

Benefits:

- Better representation

- Still maps to GEMMs → GPU-friendly

7. Feed-Forward Network (MLP)

Typical form:

| |

Modern variants:

- GELU / SiLU

- SwiGLU / GeGLU (used in LLaMA, Mistral)

Key facts:

- FFN often costs more FLOPs than attention

- Extremely GEMM-heavy

- Memory bandwidth sensitive

8. Normalization & Residuals

LayerNorm / RMSNorm

- Stabilizes training

- RMSNorm removes mean → cheaper

Residual Connections

- Enable deep networks

- Improve gradient flow

- Important for numerical stability

9. Positional Information

Since attention is permutation-invariant, position must be injected.

Common approaches

- Absolute embeddings (older)

- RoPE (Rotary Positional Embedding) ← dominant today

- ALiBi (linear bias)

RoPE:

- Enables better extrapolation to long context

- Implemented inside Q/K projection

10. Tokenization & Embeddings

Tokenization

- BPE / SentencePiece

- Subword-based

- Vocabulary ~32k–100k

Embedding Layer

- Token ID → dense vector

- Often tied with output projection weights

11. Training Objective

LLMs are trained with:

| |

Objective:

| |

Training:

- Teacher forcing

- Massive batch sizes

- Trillions of tokens

12. Scaling Laws (Why Size Matters)

Empirical laws:

Performance scales smoothly with:

- Model size

- Dataset size

- Compute budget

This motivates:

- Bigger models

- Better parallelism

- Memory optimization

13. Parallelism Strategies (System-Level Critical)

Modern LLMs cannot fit or run on one GPU.

Parallelism types

- Data Parallelism (DP)

- Tensor Parallelism (TP) – split matrices

- Pipeline Parallelism (PP) – split layers

- Sequence Parallelism

- Expert Parallelism (MoE)

Frameworks:

- Megatron-LM

- DeepSpeed

- FSDP

- NCCL underneath all of them

14. Mixture of Experts (MoE)

Instead of dense FFN:

| |

Benefits:

- More parameters

- Same compute cost

- Harder to scale (communication heavy)

Used in:

- Mixtral

- Switch Transformer

15. Inference-Time Architecture Changes

KV Cache

- Cache K/V from previous tokens

- Reduces attention cost from O(T²) → O(T)

Autoregressive Loop

| |

Bottlenecks

- Memory bandwidth

- Small batch sizes

- Kernel launch overhead

16. Performance-Critical Kernels (GPU View)

At the lowest level, everything reduces to:

- GEMM

- Softmax

- LayerNorm

- Memory movement

Optimizations:

- FlashAttention

- Fused kernels

- Tensor Cores (FP16 / BF16 / FP8)

- CUDA Graphs

- NCCL collectives

17. Summary Stack (One Slide Mental Model)

| |

Attention layer

We consider multihead self attention:

$$ X_{t,d}\quad\text{shaped}\quad [T,D] $$$$ W^Q_{d1,d2},W^K_{d1,d2},W^V_{d1,d2}\quad\text{shaped}\quad [D,D] $$$$ W^Q_{d1,d2},W^K_{d1,d2},W^V_{d1,d2}\quad\text{shaped}\quad [D,D] $$QKV:

$$ \begin{aligned} Q_{t,d} &= X_{t,d1}W^Q_{d1,d}\\ K_{t,d} &= X_{t,d1}W^K_{d1,d}\\ V_{t,d} &= X_{t,d1}W^V_{d1,d}\\ \end{aligned} $$Multihead reshaping:

$$ \begin{aligned} Q_{t,h,dh}&\\ K_{t,h,dh}&\\ V_{t,h,dh}& \quad {shaped}\quad [T,H,D/H] \end{aligned} $$$$ S_{t1,t2,h} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{D/H}} Q_{t1, h, dh} K_{t2, h, dh} \quad \text{(no sum on h)} $$$$ A_{t1,t2,h} = \text{softmax}(S_{t1,t2,h}, t2) $$$$ O_{t,h, dh} = A_{t, t1, h} V_{t1, h, dh} \quad \text{(no sum on h)} $$$$ O_{t, d} $$$$ Y_{t,d} = O_{t,d1} W^O_{d1,d} $$Backward

$$ \pdv{L}{Y_{t,d}} $$$$ \pdv{Y_{t,d2}}{W^O_{d1,d3}} = O_{t,d1} \delta_{d2,d3} $$We have

$$ \pdv{L}{W^O_{d1,d}} = \pdv{L}{Y_{t,d2}} \pdv{Y_{t,d2}}{W^O_{d1,d}} = \pdv{L}{Y_{t,d2}} O_{t,d1} \delta_{d2,d} = \pdv{L}{Y_{t,d}} O_{t,d1} $$$$ \pdv{L}{W^O_{d1,d}} = \pdv{L}{Y_{t,d}} O_{t,d1} \Box $$Similarly

$$ \pdv{L}{O_{t,d1}} = \pdv{L}{Y_{t,d}} W^O_{d1,d} \Box $$Then

$$ \pdv{L}{V_{t1, h, dh}} = \pdv{L}{O_{t,h, dh}} A_{t, t1, h} \quad \text{(no sum on h)} \Box $$$$ \pdv{L}{A_{t, t1, h}} = \pdv{L}{O_{t,h, dh}} V_{t1, h, dh} \quad \text{(no sum on h)} \Box $$$$ \pdv{L}{S_{t, t1, h}} = \text{softmax_grad}\left(\pdv{L}{A_{t, t1, h}}, A_{t, t1, h}\right) \Box $$Then

$$ \pdv{L}{Q_{t1, h, dh}} = \pdv{L}{S_{t1,t2,h}} \frac{1}{\sqrt{D/H}} K_{t2, h, dh} \quad \text{(no sum on h)} \Box $$$$ \pdv{L}{K_{t2, h, dh}} = \pdv{L}{S_{t1,t2,h}} \frac{1}{\sqrt{D/H}} Q_{t1, h, dh} \quad \text{(no sum on h)} \Box $$At last:

$$ \begin{aligned} \pdv{L}{W^Q_{d1,d}} & = \pdv{L}{Q_{t,d}} X_{t,d1} \Box \\ \pdv{L}{W^K_{d1,d}} & = \pdv{L}{K_{t,d}} X_{t,d1} \Box \\ \pdv{L}{W^V_{d1,d}} & = \pdv{L}{V_{t,d}} X_{t,d1} \Box \\ \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} \pdv{L}{X_{t,d1}} & = \pdv{L}{Q_{t,d}} W^Q_{d1,d} \Box \\ & + \pdv{L}{K_{t,d}} W^K_{d1,d} \Box \\ & + \pdv{L}{V_{t,d}} W^V_{d1,d} \Box \\ \end{aligned} $$Flash attention

For each output element ($O_{t,:}$):

Softmax for row (i):

\[ \text{softmax}(s_{ij}) = \frac{e^{s_{ij}}}{\sum_k e^{s_{ik}}} \]This can be computed incrementally.

Maintain running statistics

For query (i), process keys in blocks:

- Running max: \(m\)

- Running normalization: \(l = \sum e^{s - m}\)

- Running output accumulator: \(o\)

Initialize

\[ m = -\infty,\quad l = 0,\quad o = 0 \]For each block of keys (K_b, V_b)

- \[ s_b = q_i K_b^\top \]

- \[ m_{\text{new}} = \max(m, \max(s_b)) \]

- \[ \alpha = e^{m - m_{\text{new}}} \]

- \[ l = l \cdot \alpha + \sum e^{s_b - m_{\text{new}}} \]

- \[ o = o \cdot \alpha + \sum e^{s_b - m_{\text{new}}} \cdot V_b \]

Set \(m = m_{\text{new}}\)

CPU HPC

1. CPU & Core Architecture

Q: What matters more for HPC: core count or clock frequency? A: Depends on workload.

- Compute-bound → higher clock, wider vector units

- Memory-bound → memory bandwidth + cache

- Latency-sensitive → fewer, faster cores often win

Q: What are SIMD / vector units and why do they matter? A:

- AVX2 (256-bit), AVX-512 (512-bit)

- One instruction operates on many data elements

- Essential for CFD, linear algebra, stencil codes Missing vectorization can cause 5–10× slowdown.

Q: Why does AVX-512 sometimes reduce frequency? A:

- AVX-512 increases power & thermal load

- CPUs often downclock to stay within limits

- Can hurt mixed scalar + vector workloads

2. Memory System & NUMA

Q: What is NUMA and why does it matter? A:

- Memory is attached to CPU sockets

- Local memory ≫ remote memory in bandwidth & latency

- Bad NUMA placement can cost 2× slowdown

Q: What is “first-touch” memory policy? A:

- Memory is allocated on the NUMA node of the first thread that writes it

- Initialize arrays in parallel with correct binding

Q: How many memory channels should be populated? A:

- Always all channels

- Bandwidth scales almost linearly with channels

- Example: EPYC (12 channels) → missing DIMMs = wasted performance

Q: Why is my scaling bad even though CPUs are idle? A:

- Memory bandwidth saturation

- Cache thrashing

- NUMA imbalance

- False sharing

3. Cache Hierarchy

Q: What is cache blocking / tiling? A:

- Reorganize loops so working set fits into cache

- Crucial for matrix ops and stencils

Q: What is false sharing? A:

- Multiple threads write to different variables in the same cache line

- Causes cache line ping-pong

- Fix with padding or structure reordering

Q: Why does L3 cache sometimes hurt performance? A:

- Shared L3 can become a contention point

- Cross-core traffic increases latency

4. Parallel Programming Models

Q: MPI vs OpenMP: when to use which? A:

- MPI: distributed memory, multi-node

- OpenMP: shared memory, intra-node

- Best practice: MPI + OpenMP hybrid

Q: Why hybrid MPI+OpenMP instead of pure MPI? A:

- Reduces MPI rank count

- Better memory locality

- Less communication overhead

Q: How many MPI ranks per node should I use? A:

- Often 1 rank per NUMA domain

- Or per socket

- Rarely 1 rank per core for memory-heavy codes

5. Thread & Process Binding

Q: Why does binding matter? A:

- Prevents thread migration

- Improves cache reuse

- Avoids NUMA penalties

Q: What is core affinity vs NUMA affinity? A:

- Core affinity: bind threads to cores

- NUMA affinity: bind memory + threads to node

Q: What happens if I don’t bind processes? A:

- OS may migrate threads

- Cache invalidation

- Unpredictable performance

6. Scaling & Performance

Q: Why does strong scaling stop working? A:

- Communication dominates computation

- Memory bandwidth limit

- Load imbalance

Q: Why does performance drop when using more cores? A:

- Bandwidth saturation

- Cache contention

- NUMA traffic

- Frequency throttling

Q: What is Amdahl’s Law in practice? A:

- Small serial sections dominate at scale

- Even 1% serial → max 100× speedup

7. Compiler & Toolchain

Q: Does compiler choice matter? A: Yes, a lot.

- GCC, Clang, Intel, AOCC generate different vector code

- Auto-vectorization quality varies

Q: Which compiler flags matter most? A:

-O3-march=native/-xHost-ffast-math(if allowed)- Vectorization reports (

-fopt-info-vec)

Q: Why does debug build run 10× slower? A:

- No inlining

- No vectorization

- Extra bounds checks

8. MPI & Communication

Q: Why is MPI slow inside a node? A:

- Shared memory transport not enabled

- Too many ranks

- NUMA-unaware placement

Q: What is eager vs rendezvous protocol? A:

- Small messages: eager (buffered)

- Large messages: rendezvous (handshake + RDMA)

Q: Why does message size matter so much? A:

- Latency dominates small messages

- Bandwidth dominates large ones

9. Power, Frequency & Thermal Effects

Q: Why does my CPU run slower at full load? A:

- Power limits

- Thermal throttling

- AVX frequency offset

Q: Should I disable turbo boost? A:

- Sometimes yes for stability

- Sometimes no for latency-sensitive work

- Benchmark both

10. Profiling & Diagnostics

Q: How do I know if I’m memory-bound? A:

- Low IPC

- Flat performance with more cores

- Hardware counters: bandwidth near peak

Q: What tools are commonly used? A:

perf- VTune / uProf

- LIKWID

- MPI profilers (mpiP, Score-P)

11. Storage & I/O

Q: Why does parallel I/O scale poorly? A:

- Metadata contention

- Small I/O operations

- File locking

Q: MPI-IO vs POSIX I/O? A:

- MPI-IO supports collective buffering

- POSIX often simpler but less scalable

12. Common “Gotchas”

Q: Why does my code run faster with fewer cores? A:

- Cache fits

- Less NUMA traffic

- Higher frequency

Q: Why does performance differ across nodes? A:

- BIOS settings

- Memory population

- Thermal conditions

- Background daemons

C++

1. Core C++ Language Fundamentals (Must-know)

These are baseline expectations. You should be able to explain them clearly and concisely.

Object Lifetime & RAII

RAII principle: resource acquisition is initialization

Constructors / destructors control ownership

Why RAII is critical for:

- Memory

- File handles

- CUDA resources (

cudaMalloc, streams, events)

Example explanation:

“RAII ensures exception safety and deterministic cleanup, which is essential for long-running HPC or GPU jobs.”

Copy vs Move Semantics

Rule of 0 / 3 / 5

When move is invoked:

- Returning by value

std::vector::push_back

Difference between:

- Copy constructor

- Move constructor

- Copy elision (RVO / NRVO)

Key interview point:

- Why move semantics reduce allocation + memcpy

- When move is not free (e.g., deep ownership, ref-counted memory)

References & Pointers

T*vsT&const T*vsT* constconst T&for function arguments- Dangling references and lifetime issues

2. Memory Management

Stack vs Heap

Stack:

- Fast

- Limited size

- Automatic lifetime

Heap:

- Explicit allocation

- Fragmentation

- NUMA considerations (important in HPC)

You should know:

- When stack allocation is preferred

- Why large arrays go on heap

new/delete vs malloc/free

new:- Calls constructors

- Type-safe

malloc:- Raw memory

- No constructors

Why mixing them is UB

DevTech angle:

- CUDA uses C-style APIs → careful ownership handling

Smart Pointers

std::unique_ptr- Exclusive ownership

- Zero overhead abstraction

std::shared_ptr- Ref-counting overhead

- Atomic ops

std::weak_ptr

Common pitfall question:

“Why is

shared_ptrdangerous in performance-critical code?”

Alignment & Padding

alignas- Cache-line alignment (64B)

- False sharing

You should be ready to explain:

- Why misalignment hurts SIMD / GPU transfers

- How aligned allocation improves bandwidth

3. Const-Correctness (Often Tested Verbally)

You should be fluent in:

| |

Why it matters:

- Express intent

- Enables compiler optimizations

- API design clarity

DevTech angle:

- Large codebases + customer code → const safety matters

4. Templates & Compile-Time Concepts (Medium Depth)

You don’t need TMP wizardry, but must understand basics.

Function & Class Templates

- Template instantiation

- Header-only requirement (usually)

typenamevsclass

constexpr

- Compile-time evaluation

- Difference between

constexprandconst

Useful example:

- Fixed tile sizes

- Static array dimensions

- Kernel configuration parameters

SFINAE / Concepts (High-level only)

- What problem they solve

- Why concepts improve error messages

You don’t need to write them, but explain why they exist.

5. STL & Performance Awareness

Containers

You should know complexities and memory layouts:

| Container | Notes |

|---|---|

std::vector | Contiguous, cache-friendly |

std::deque | Non-contiguous |

std::list | Bad for cache |

std::unordered_map | Hash cost, poor locality |

std::map | Tree, O(log n) |

DevTech emphasis:

- Why

vectoris almost always preferred - When

unordered_mapis a bad idea

Iterators & Algorithms

- Prefer algorithms (

std::transform,std::reduce) - Iterator invalidation rules

6. Concurrency & Thread Safety (Important)

std::thread, mutex, atomic

- Data races vs race conditions

- Mutex vs atomic trade-offs

- False sharing

DevTech angle:

- CPU-side orchestration of GPU work

- MPI + threading interaction

Memory Model (High-level)

- Sequential consistency

- Relaxed atomics (know they exist)

- Why atomics are expensive

7. C++ & ABI / Toolchain Awareness (DevTech-specific)

You stand out if you know these.

- ABI compatibility

libstdc++vslibc++- ODR violations

- Static vs dynamic linking

Very relevant given your HPC + distribution experience.

8. C++ + CUDA Awareness (Big Plus)

You don’t need kernel details, but:

- Host vs device code

__host__ __device__- POD types for device transfers

- Why virtual functions are problematic on device

RAII with CUDA:

| |

9. Common Interview “Explain” Questions

Prepare crisp answers to:

- Why is RAII better than manual cleanup?

- Difference between

constandconstexpr - When would you avoid

shared_ptr? - Why does

vectorreallocation invalidate pointers? - What causes undefined behavior?

- Why is cache locality important?

C++ threading

1. std::thread, std::mutex, std::atomic

std::thread

- Represents a native OS thread

- Executes a callable concurrently

| |

Key points:

Threads run in parallel on multi-core CPUs

Programmer is responsible for:

- Synchronization

- Lifetime (

join()ordetach())

DevTech angle:

- Often used for CPU-side orchestration (I/O, MPI progress, GPU launches)

- Creating many threads is expensive → use thread pools

std::mutex

- Provides mutual exclusion

- Ensures only one thread enters a critical section at a time

| |

Key points:

- Blocks threads → context switches

- Must avoid deadlocks

- Use RAII (

std::lock_guard,std::unique_lock)

std::atomic<T>

- Provides lock-free operations on a single variable

| |

Key points:

- Guarantees no data races

- Uses CPU atomic instructions

- Limited to simple operations

2. Data Races vs Race Conditions (Very Common Interview Question)

Data Race (Undefined Behavior ⚠️)

A language-level concept.

Two threads access the same memory location without synchronization, and at least one access is a write.

| |

Characteristics:

- Undefined behavior

- Compiler may reorder or optimize aggressively

- Can produce seemingly correct results sometimes

Race Condition (Logical Bug)

A program logic issue.

Program correctness depends on timing or interleaving of threads.

| |

Characteristics:

- May still be data-race-free

- Produces wrong results

- Deterministic under some schedules, wrong under others

Relationship

| Concept | Level | UB? |

|---|---|---|

| Data race | C++ memory model | Yes |

| Race condition | Algorithm logic | No |

💡 All data races are race conditions, but not all race conditions are data races.

3. Mutex vs Atomic — Trade-offs

Mutex

Pros

- Works for complex critical sections

- Easy to reason about

- Strong synchronization guarantees

Cons

- Blocking

- Context switches

- Cache-line bouncing

- Poor scalability under contention

| |

Atomic

Pros

- Non-blocking

- Very fast for low contention

- Scales better for counters, flags

Cons

- Limited operations

- Harder to reason about

- Still expensive under heavy contention

| |

Performance Comparison

| Aspect | Mutex | Atomic |

|---|---|---|

| Blocking | Yes | No |

| Context switch | Possible | No |

| Complexity | Low | Higher |

| Scalability | Poor (contention) | Better |

| Use case | Complex state | Counters / flags |

DevTech rule of thumb:

Use atomics for simple state, mutexes for complex invariants.

4. False Sharing (Very Important for HPC)

What is False Sharing?

- Two threads modify different variables

- Variables reside on the same cache line

- Causes unnecessary cache invalidations

| |

Even though a and b are independent:

- Cache line ping-pongs between cores

- Performance collapses

Why It Hurts Performance

- Cache coherence protocol invalidates entire cache line

- High-frequency writes → massive traffic

- Especially bad on NUMA systems

How to Fix It

Padding

| |

Or use padding explicitly

| |

Common in:

- Thread-local counters

- Work queues

- Performance monitoring

Can cause 10× slowdowns with no visible bug

Interview one-liner:

“False sharing doesn’t break correctness, but it kills scalability.”

5. Memory Ordering (Bonus, High-Level)

You don’t need details, but know:

memory_order_relaxed→ no ordering, just atomicitymemory_order_acquire/release→ synchronization- Default is

seq_cst(strongest, slowest)

CUTLASS, CUB and more

CUB (CUDA UnBound)

Purpose: High-performance parallel primitives for CUDA.

Provides building blocks like:

scan(prefix sum)reducesort(radix sort)histogramselect,partition

Focuses on thread / warp / block / device-level primitives.

Header-only, template-based.

Used when you are writing custom CUDA kernels and need fast, correct primitives.

Abstraction level: 👉 Low–mid level (kernel author productivity + performance)

Example use cases:

- Implementing your own algorithms (e.g. graph, CFD, ML ops)

- Writing custom CUDA kernels that need scans/sorts

- Often used inside other libraries (Thrust, PyTorch, etc.)

CUTLASS (CUDA Templates for Linear Algebra Subroutines)

Purpose: High-performance GEMM / tensor contraction kernels.

Specializes in:

- GEMM (matrix multiply)

- Convolutions

- Tensor contractions

Heavily optimized for:

- Tensor Cores

- MMA / WMMA instructions

- Memory tiling, pipelining

Template-heavy, meta-programming driven.

Often used to generate kernels, not called like a normal library.

Abstraction level: 👉 Mid–low level (near-hardware math kernels)

Example use cases:

- Deep learning frameworks (cuBLAS uses similar ideas)

- Writing custom GEMM kernels

- Research / tuning kernel performance

One-line comparison

| Library | Main role | Typical ops | Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| CUB | Parallel primitives | scan, reduce, sort | Algorithm / kernel |

| CUTLASS | Linear algebra kernels | GEMM, conv | Math / tensor core |

How they relate in practice

- CUB → general-purpose GPU algorithms

- CUTLASS → specialized math kernels

- Frameworks like PyTorch / cuBLAS / cuDNN internally use ideas or code from both.

PyTorch

1. Tensors (the core data structure)

What is a tensor?

A torch.Tensor is:

- An n-dimensional array

- With device (CPU / CUDA)

- dtype (float32, float16, int64, …)

- layout (strided, sparse, etc.)

- autograd metadata (for gradient tracking)

| |

Key attributes

| |

Tensor creation

| |

⚠️ from_numpy shares memory → modifying one affects the other.

View vs Copy (VERY IMPORTANT)

| Operation | Behavior |

|---|---|

view() | No copy (requires contiguous) |

reshape() | View if possible, else copy |

transpose() | View (changes stride) |

clone() | Deep copy |

detach() | Shares data, drops autograd |

| |

Contiguity & strides

| |

Many CUDA kernels require contiguous tensors:

| |

2. Autograd (Automatic Differentiation)

Dynamic computation graph

PyTorch builds the graph at runtime:

- Each tensor stores a

grad_fn - Graph is re-created every forward pass

| |

Graph nodes:

| |

Leaf vs non-leaf tensors

| |

Only leaf tensors accumulate .grad by default.

To keep grad for non-leaf:

| |

Gradient accumulation

| |

⚠️ Forgetting zero_grad() → wrong gradients.

Disabling autograd

Used for inference / evaluation:

| |

Or permanently:

| |

3. Backward pass mechanics

backward()

| |

- Computes ∂loss/∂leaf

- Frees graph by default

To reuse graph:

| |

Custom gradients

| |

Used when:

- Writing custom CUDA ops

- Fusing ops

- Non-standard backward logic

4. Modules (nn.Module)

What is a Module?

A stateful computation unit:

- Parameters (

nn.Parameter) - Buffers (running stats)

- Submodules

| |

Parameters vs buffers

| |

| Type | Trained | Saved | Device moved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Buffer | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

Train vs Eval mode

| |

Affects:

DropoutBatchNormLayerNorm(partially)

5. Losses & Optimizers

Loss functions

| |

⚠️ Do NOT apply softmax before CrossEntropyLoss

Optimizers

| |

Optimizer updates parameters, not tensors.

6. CUDA & device semantics

Moving tensors

| |

Model and input must be on same device.

Async execution

CUDA ops are asynchronous:

| |

Useful for timing.

Mixed precision

| |

Reduces memory + increases throughput.

7. In-place operations (⚠️ important)

| |

Problems:

- Can break autograd

- Can overwrite values needed for backward

Safe rule:

Avoid in-place ops on tensors requiring grad unless you know the graph.

8. Common tensor ops (you MUST know)

Broadcasting

| |

Reduction

| |

Indexing

| |

9. Data loading

| |

Key ideas:

- Lazy loading

- Multi-worker

- Pinned memory for CUDA

| |

10. Typical training loop (canonical)

| |

11. Mental model (important for interviews)

PyTorch philosophy

- Define-by-run

- Python controls graph

- Easy debugging

- Slight overhead vs static graphs

Key invariants

- Tensors carry gradient history

- Graph is dynamic

- Gradients accumulate

- Optimizer owns parameter updates

- Device consistency is mandatory

Internet

The Big Picture

Think of networking like sending a letter:

- You write a message (application)

- Put it in envelopes with addresses and tracking info (transport & internet)

- The postal system moves it physically (link & physical)

Each layer wraps (encapsulates) the data from the layer above.

TCP/IP Model (What the Internet Actually Uses)

This is the practical model with 4 layers.

1️⃣ Application Layer

What it does: Defines how applications talk to the network.

Examples:

- HTTP / HTTPS – web

- FTP / SFTP – file transfer

- SMTP / IMAP / POP3 – email

- DNS – name → IP resolution

- SSH – remote login

Key idea:

- Application protocols define message formats and semantics

- They do not care how data is routed or transmitted

2️⃣ Transport Layer

What it does: Provides end-to-end communication between processes.

Main protocols:

TCP (Transmission Control Protocol)

- Reliable

- Ordered

- Congestion-controlled

- Stream-based

UDP (User Datagram Protocol)

- Unreliable

- No ordering

- Low latency

- Message-based

Responsibilities:

- Ports (e.g., HTTP uses port 80)

- Segmentation & reassembly

- Flow control

- Error recovery (TCP)

- Congestion control (TCP)

Key distinction:

IP talks to machines, TCP/UDP talk to processes

3️⃣ Internet Layer

What it does: Moves packets between machines across networks.

Main protocol:

- IP (Internet Protocol)

Responsibilities:

- Logical addressing (IP addresses)

- Routing across networks

- Packet fragmentation (IPv4)

Supporting protocols:

- ICMP – errors, diagnostics (

ping) - ARP – IP → MAC mapping (local network)

- IPsec – security at IP level

Key idea:

- IP is best-effort: no guarantees of delivery or order

4️⃣ Link Layer

What it does: Moves frames within a single physical network.

Examples:

- Ethernet

- Wi-Fi (802.11)

- Cellular

- PPP

Responsibilities:

- MAC addressing

- Framing

- Error detection (CRC)

- Medium access (CSMA/CD, CSMA/CA)

Key idea:

- This layer is local only (no routing)

OSI Model (Conceptual Reference)

The OSI model has 7 layers, mainly used for teaching and reasoning.

| OSI Layer | TCP/IP Equivalent |

|---|---|

| 7 Application | Application |

| 6 Presentation | Application |

| 5 Session | Application |

| 4 Transport | Transport |

| 3 Network | Internet |

| 2 Data Link | Link |

| 1 Physical | Link |

Extra OSI layers explained

- Presentation: encoding, compression, encryption (e.g., TLS fits here conceptually)

- Session: session management, checkpoints, recovery

In practice, these are merged into the application layer.

Encapsulation Example (HTTP Request)

When you load a webpage:

| |

On receive, the process is reversed.

Where Common Technologies Fit

| Technology | Layer |

|---|---|

| TLS / SSL | Between Application & Transport |

| NAT | Internet / Link boundary |

| Firewall | Internet / Transport |

| Load Balancer | Transport or Application |

| VPN | Internet or Application |

Important Mental Models

Layer Independence

- Each layer only relies on the layer below

- Changes in Wi-Fi don’t affect HTTP

End-to-End Principle

- Reliability belongs at the endpoints, not the network (why IP is simple)

Best-effort Core

- The Internet core is unreliable

- Intelligence lives at the edges (TCP, apps)

Minimal Summary

| |

HPC general

Roofline model

Memory hierarchies

CPU

2.1 Typical CPU hierarchy (x86 / ARM)

| |

2.2 Key properties

🔹 Registers

- Latency: ~1 cycle

- Scope: per hardware thread

- Managed by: compiler + ISA

🔹 L1 Cache

Latency: ~3–5 cycles

Size: ~32–64 KB

Policy:

- Write-back

- Hardware-managed

Fully coherent

🔹 L2 Cache

- Latency: ~10–15 cycles

- Size: ~256 KB – 2 MB

- Still private or semi-private

- Hardware-prefetched

🔹 L3 Cache (LLC)

- Latency: ~30–60 cycles

- Size: tens of MB

- Shared across cores

- Critical for NUMA locality

🔹 Main Memory (DRAM)

Latency: ~80–120 ns (~200–300 cycles)

Bandwidth: ~50–200 GB/s (socket-level)

NUMA effects:

- Local vs remote memory access costs differ

2.3 Coherence & consistency (very important)

Cache coherence: MESI/MOESI

Consistency model:

- x86: strong (TSO-like)

- ARM: weaker, explicit barriers

Programmer experience:

- You assume a single coherent address space

- Synchronization primitives (mutex, atomic) enforce ordering

2.4 Programmer visibility

| Level | Visible to programmer? |

|---|---|

| Registers | Yes |

| L1/L2/L3 | ❌ (mostly implicit) |

| Prefetch | Optional intrinsics |

| NUMA | Yes (first-touch, numa_alloc) |

CPU philosophy:

Hide memory hierarchy as much as possible.

GPU

GPU hierarchy is explicit, throughput-oriented, and programmer-visible.

3.1 Typical GPU hierarchy (NVIDIA-like)

| |

3.2 Key components

🔹 Registers

Latency: 1 cycle

Scope: per thread

Size pressure:

- Limits occupancy

Spilling → local memory (in VRAM!)

🔹 Shared Memory

- Latency: ~10–20 cycles

- Size: ~64–228 KB per SM (configurable)

- Explicitly managed

- Banked SRAM

Used for:

- Tiling

- Data reuse

- Inter-thread cooperation

This has no CPU equivalent.

🔹 L1 Cache

- Often unified with shared memory

- Caches global loads

- Not coherent across SMs

🔹 L2 Cache

- Latency: ~200 cycles

- Size: ~10–100 MB (modern GPUs)

- Globally shared

- Atomic operations resolved here

- Coherent across SMs

🔹 Global Memory (VRAM)

Latency: ~400–800 cycles

Bandwidth:

- GDDR6: ~500–1000 GB/s

- HBM3: >3 TB/s

Access pattern sensitive:

- Coalescing is critical

🔹 Local Memory (misleading name)

Thread-private but physically in VRAM

Triggered by:

- Register spill

- Large arrays

Very slow

🔹 Host Memory (CPU RAM)

Accessed via:

- PCIe (~16–64 GB/s)

- NVLink (much faster)

CUDA Unified Memory can migrate pages

3.3 Coherence & consistency

No global cache coherence

Explicit synchronization:

__syncthreads()- memory fences

Atomics scoped:

- thread / block / device / system

Memory model is weak by default

GPU philosophy:

Expose memory hierarchy so programmers can control it.

| Aspect | CPU | GPU |

|---|---|---|

| Core count | Few (8–128) | Many (10k+ threads) |

| Latency hiding | Caches + OoO | Massive multithreading |

| Cache management | Hardware | Mostly explicit |

| Shared memory | ❌ | ✔ |

| Cache coherence | Strong | Limited |

| Bandwidth focus | Moderate | Extreme |

| Memory model | Stronger | Weaker |

| Programmer control | Low | High |

Performance analysis

1. Fundamental axes of profiling

Every profiler sits somewhere along these axes:

(A) How data is collected

- Sampling: periodically interrupts execution (PC / stack / counters)

- Instrumentation: inserts hooks around functions, regions, APIs

- Tracing: records every event (often timestamped)

(B) What is being observed

- Control flow (where time goes)

- Microarchitecture (why it is slow)

- Concurrency & overlap (what runs in parallel, what waits)

- Communication (who talks to whom, how much, when)

- Memory behavior (latency, bandwidth, locality)

(C) Level of abstraction

- Instruction / micro-op

- Function / call stack

- Runtime API (CUDA, MPI, OpenMP)

- Algorithmic phase / region

- System-wide (CPU ↔ GPU ↔ NIC ↔ filesystem)

2. What different classes of tools actually tell you

2.1 Stack sampling profilers (perf, py-spy, async-profiler)

What they do

- Periodically sample PC + call stack

- Optionally attach hardware counters to samples

What you get

- 🔥 Flame graphs (inclusive/exclusive time)

- Hot functions and call paths

- Time distribution across code paths

What they are good for

- “Where does time go?”

- Unexpected hotspots

- Regression detection

- Works even on uninstrumented binaries

What they cannot tell you

- Exact ordering or overlap

- Per-event latency

- MPI/GPU causality

- Fine-grained synchronization behavior

Typical insights

- A “small” helper function dominating runtime

- Python/C++ boundary overhead

- Poor inlining / abstraction cost

- Load imbalance (indirectly)

perf answers: “Where am I burning cycles?”

2.2 Hardware counter–driven profilers (perf, VTune, LIKWID, PAPI)

What they do

Sample or count PMU events

- cache misses

- branch mispredicts

- memory bandwidth

- stalls (frontend/backend)

- vectorization usage

What you get

- CPI breakdowns

- Cache miss rates per function

- Roofline placement

- NUMA locality info

What they are good for

- “Why is this loop slow?”

- Memory-bound vs compute-bound

- Vectorization effectiveness

- NUMA / cache pathologies

- False sharing

What they cannot tell you

- Algorithmic correctness

- Timeline causality

- GPU kernel behavior

- Communication semantics

Typical insights

- L3 misses dominate → bandwidth-bound

- Scalar remainder loop killing SIMD

- Remote NUMA access dominating stalls

These tools answer: “What microarchitectural wall am I hitting?”

2.3 Timeline / tracing tools (Nsight Systems, VTune timeline, TAU trace)

What they do

Record timestamped events

- CPU threads

- GPU kernels

- Memcpy / DMA

- CUDA API calls

- MPI calls

- Synchronization events

What you get

- 📊 Unified timelines

- Overlap visualization (CPU–GPU, comm–compute)

- Idle / wait regions

- Dependency chains

What they are good for

- “Are things overlapping as I expect?”

- Pipeline bubbles

- Synchronization bottlenecks

- CPU–GPU orchestration quality

- MPI wait vs compute time

What they cannot tell you

- Deep microarchitectural causes

- Precise per-instruction behavior

- Cache-level detail (usually)

Typical insights

- GPU idle waiting for CPU launch

- MPI ranks stuck in

MPI_Wait - Memcpy serialization

- Too many small kernels / launches

nsys answers: “What happens when?”

2.4 GPU kernel profilers (Nsight Compute, rocprof, OmniPerf)

What they do

Instrument or replay kernels

Collect SM-level metrics

- occupancy

- warp stalls

- memory transactions

- instruction mix

What you get

- Per-kernel performance breakdown

- Warp stall reasons

- Memory coalescing efficiency

- Tensor core utilization

What they are good for

- Kernel-level optimization

- Mapping kernel to roofline

- Understanding register/shared-memory tradeoffs

What they cannot tell you

- Application-level scheduling issues

- Multi-kernel orchestration

- MPI effects

Typical insights

- Occupancy limited by registers

- Memory dependency stalls dominate

- Tensor cores underutilized

- Poor L2 reuse

These answer: “Why is this kernel slow?”

2.5 MPI-focused profilers (Scalasca, Intel Trace Analyzer, TAU MPI)

What they do

- Intercept MPI calls

- Measure message sizes, timing, partners

- Detect wait states and imbalance

What you get

- Communication matrices

- Wait-for relationships

- Load imbalance reports

- Critical-path analysis

What they are good for

- Strong/weak scaling analysis

- Communication patterns

- Synchronization inefficiencies

- Network pressure diagnosis

What they cannot tell you

- Node-local microarchitecture issues

- GPU kernel inefficiencies

- Algorithmic correctness

Typical insights

- Rank imbalance dominating runtime

- Collective operations scaling poorly

- Unexpected all-to-all patterns

- Small-message latency overhead

MPI profilers answer: “Who is waiting for whom, and why?”

2.6 Region / phase instrumentation tools (TAU, NVTX, manual timers)

What they do

- User-defined regions

- Phase-based timing & counters

What you get

- Per-algorithm phase breakdown

- Repeatable, low-noise measurements

- Cross-run comparisons

What they are good for

- Algorithmic tradeoff analysis

- Regression tracking

- Scaling studies

- Validating theoretical complexity

What they cannot tell you

- Unexpected hotspots inside regions

- Fine-grained microbehavior

Typical insights

- Preconditioner dominates solver

- Communication cost overtakes compute at scale

- Phase imbalance across ranks

These answer: “Which algorithmic phase dominates?”

3. Putting it all together (how experts actually use them)

A typical HPC performance workflow looks like this:

Stack sampling / flame graph

- Find hotspots

Timeline tracing

- Check overlap, stalls, synchronization

Hardware counters / roofline

- Determine compute vs memory limits

MPI analysis

- Identify scaling bottlenecks

Kernel-level GPU profiling

- Optimize inner loops

Each tool answers a different why-question, not the same one.

4. One-sentence cheat sheet

| Tool class | Answers |

|---|---|

| Flame graphs | Where is time spent? |

| Hardware counters | Why is this code slow on this CPU/GPU? |

| Timelines | What runs when, and what is waiting? |

| MPI profilers | Who waits for whom across nodes? |

| GPU kernel profilers | Why is this kernel inefficient? |

| Instrumentation | Which algorithmic phase dominates? |